❋Design

❉Dialogue

In Conversation with Stefi Orazi

Since 2006, London-based graphic designer Stefi Orazi has been “pushing type and images around.” However, a fascination for Modernist Architecture, anchored in nostalgia and cultivated by numerous experiences living in iconic estates throughout adulthood, has shaped an ancillary vocation that has borne five books and the much-loved platform Modernist Estates. Writer Tiffany Jade spoke with Stefi about her own Modernist narrative.

Open Journal (OJ): Where does your fascination for Modernist buildings stem from?

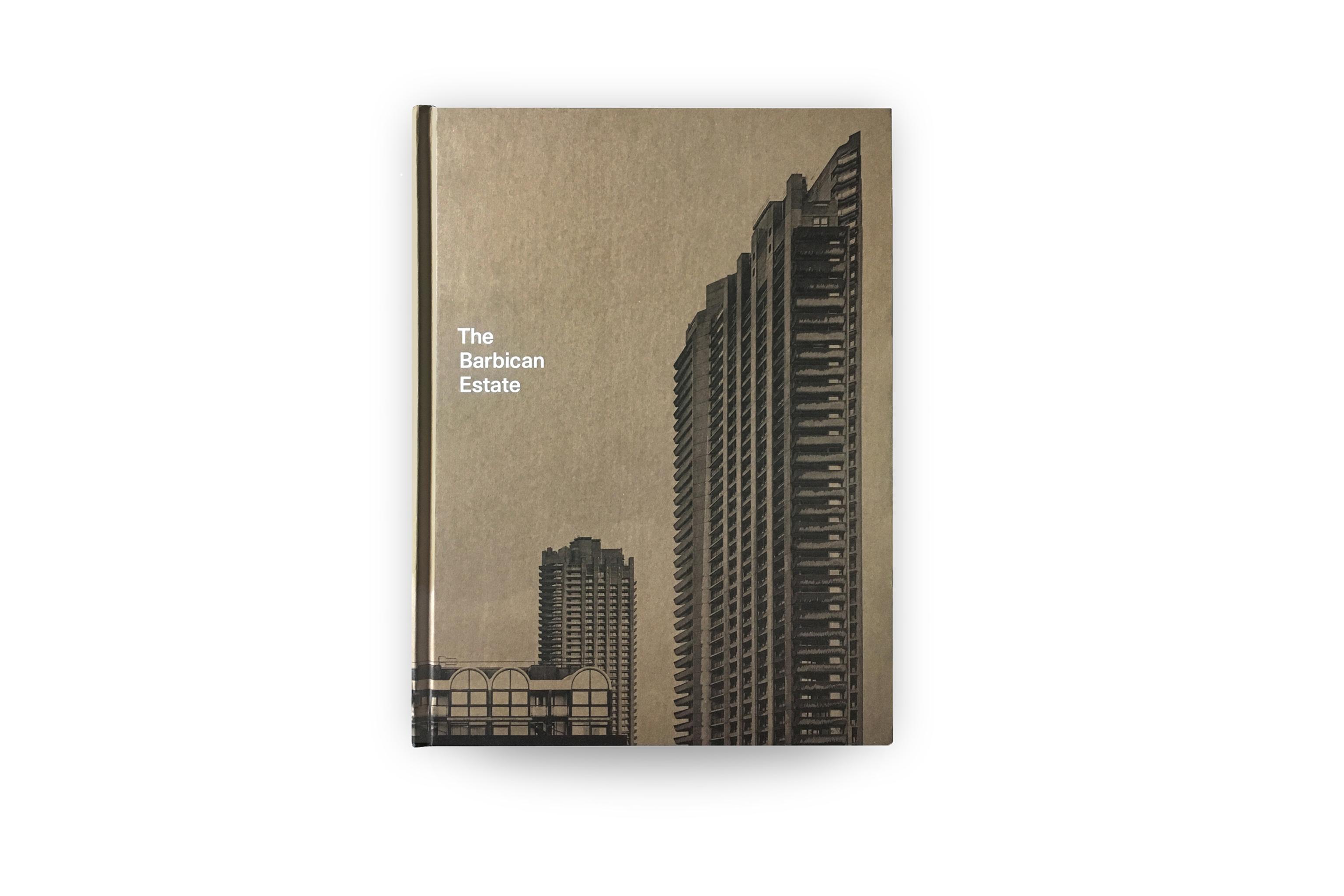

Stefi Orazi (SO): Apart from when I was very young, I’ve always lived in purpose-built flats. My school was a post-war '60s building, and my grandmother lived in a 1960s council house, so I suppose there's a certain familiarity with the architecture that, despite its hard straight lines, is comforting to me. But it wasn't until I was in my early twenties when I moved to the Barbican Estate in London that I became seriously interested in architecture and its history. It was by chance that I moved there. After graduating with a graphic design degree, I started working for a magazine in central London. The Art Director happened to have a spare room in his flat, and I rented it with short-term intentions. This was in the late '90s, and the estate and Brutalist architecture weren't anywhere near as popular as today. The flat was amazing; it's what is known as a Type 36 — essentially a duplex penthouse apartment with double-height living space as soon as you walk through the door, open tread timber staircase, original 1960s kitchen, barrel-vaulted ceilings and spacious private terrace. It was breathtaking! Especially since I had just moved out of student accommodation; I'd landed on my feet!

It's impossible to live in the Barbican and not be affected by its architecture. It's a unique place, with private gardens, a lake, a waterfall and a raised walkway snaking through it, so it's completely car-free. I ended up living in the flat for seven years before moving into a flat in the Golden Lane Estate, also designed by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, in the 1950s, and right next door to the Barbican — I was hooked!

Perambulations by Stefi Orazi.

OJ: Does the Modernist design aesthetic bleed into your graphic work too?

SO: I’m not sure about the aesthetic per se. I was a graphic designer long before I started delving deep into modernist architectural history, and aesthetically, I don't think my work has changed. I think there's a crossover in terms of thinking, though. Graphic design is about problem-solving and the organisation and efficiency of content within a limited space and budget. I have a very rational approach to this, in the same way I think modernist architects did.

More recently, I've been directly combining my interest in modernist architecture with my graphic design skills. Since 2020, I've produced a series of printed architectural walking guides called 'Perambulations' of various neighbourhoods, mostly in London. As well as writing the guides, I design them.

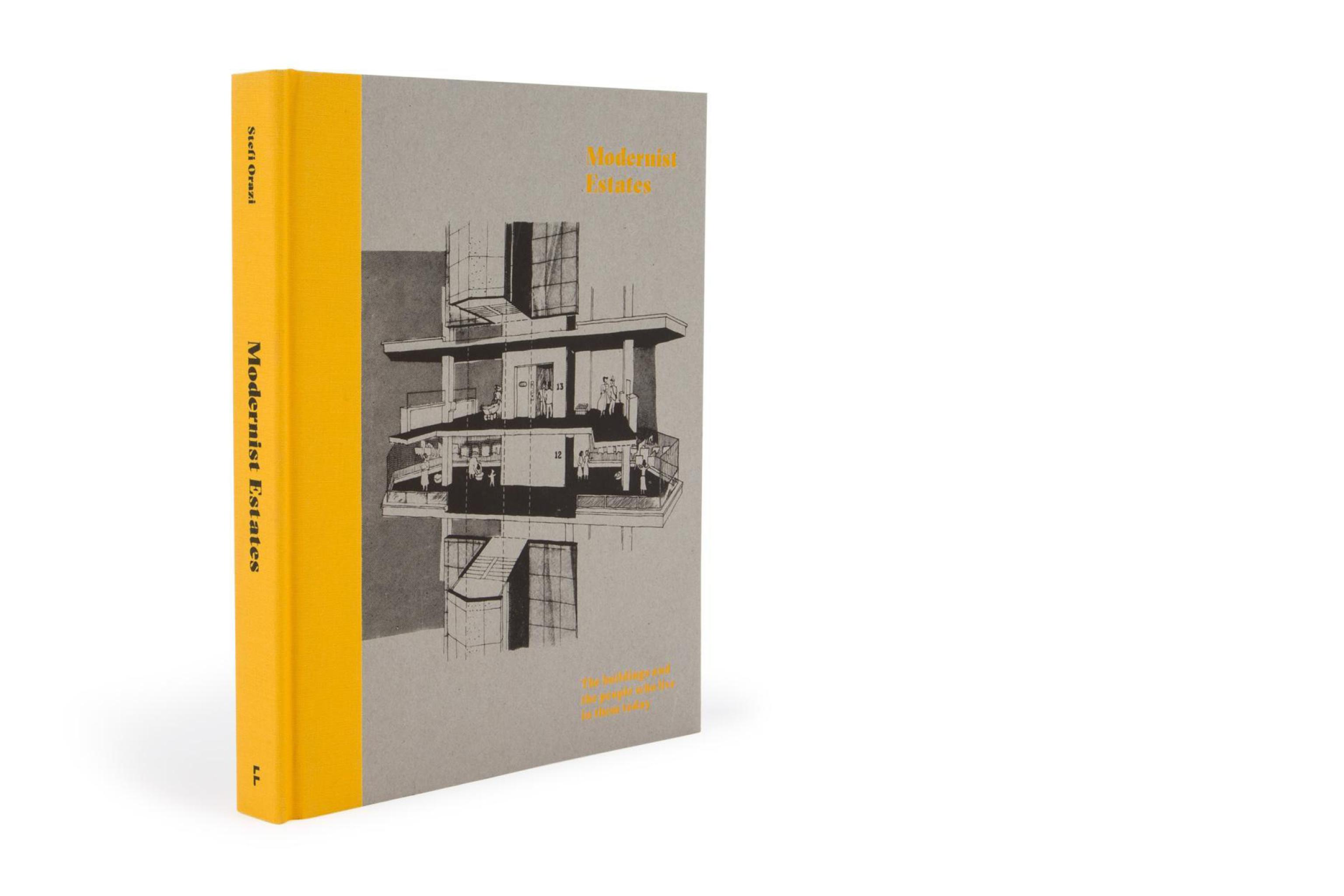

Modernist Estates by Stefi Orazi.

OJ: How did Modernist Estates begin and why?

SO: It was originally just a Tumblr blog. I started it in 2013. I was looking to move flats and buy somewhere else. I couldn't afford to stay in the same area, as I wanted something bigger. I began researching other estates in London and trawling online property sites. I'd find out their history, etc., and list them on the site. I became quite addicted when I realised how many great housing estates there are across the city. I'd post almost daily, and it soon began to get a dedicated following. A few months after starting the blog, I began a series of interviews with residents of Modernist housing estates, which led to my first book 'Modernist Estates: The Buildings and the People Who Live in Them Today', which, to my surprise, was very popular and reprinted several times. I've now written five booksThe Barbican Estate; Modernist Estates Europe; Modernist Escapes and Golden Lane Estate: An Urban Village which, as with the Perambulations series, I have also designed.

I've now turned the Tumblr blog into a property rental website where I essentially photograph modernist homes for rent on behalf of landlords and list them on the site—cutting out the need for an estate agent. Last year, I added a collection of design-focused holiday homes. These range from a self-built garden studio to a contemporary house by Marcus Lee on the Isle of Mull, to the 1960s single-storey former seaside home of musician Imogen Holst, designed by H.T. Cadbury-Brown.

The Barbican Estate by Stefi Orazi.

OJ: What is your favourite Modernist architectural oddity and why?

SO: The classical caryatids of Highpoint II—a block of luxury apartments in Highgate, London, designed by Berthold Lubetkin in the late 1930s. Highpoint I completed in 1935 is considered one of Britain's earliest modernist housing projects, and Highpoint II, finished in 1938, shares similar design principles. The planning authorities were unconvinced that the cantilevered entrance canopy of Highpoint II would not collapse. To appease them, Lubetkin bought two caryatids, cast from the Erechtheion on the Acropolis—completely at odds with modernism—from a curator at the British Museum. Lubetkin added them to 'support' the canopy—but secretly left a tiny gap between the two.

Church Walk, Aldeburgh, Suffolk by Architects H.T. Cadbury-Brown is listed on Stefi Orazi's website Modernist Estates. Image by Stefi Orazi.

OJ: How does/can Modernist Architecture influence a contemporary approach to designing within the context of the built environment? What can we take and expand upon?

SO: That’s a difficult question to answer, as I don't think all Modernist architecture was successful in the UK. I think its basic principles, such as expanses of light, functional and efficient plans, regulated space standards, and outdoor space, are relevant to contemporary architecture, but it's important not to put modernist architecture on a pedestal. With its use of concrete, the style was easy to replicate en masse cheaply. In the UK, the desperate need for more housing, following the Second World War, led to swathes of new housing estates across the country. Although often with good intentions, many were built cheaply and quickly and without the proper infrastructure in place such as shops, schools, doctors, parks, etc. Tall tower blocks, for example, were not properly maintained and were often unsuitable for families with young children. I think it's important to learn these lessons. Many of these post-war developments are being demolished but are unfortunately not necessarily being replaced with anything better and built to last.

Church Walk, Aldeburgh, Suffolk by Architects H.T. Cadbury-Brown is listed on Stefi Orazi's website Modernist Estates. Image by Stefi Orazi.

OJ: What are the social values of the environments such as those documented in Modernist Estates?

SO: The housing estates built by councils and designed by some of the country's best architects were intended for 'ordinary people'. There was a consensus that everyone deserved a decent home. After the War, damaged houses and Victorian slums were cleared and replaced with modern homes. There was a concerted effort by the state and the private sector to improve the lives of everyone in society, including the very poor. I think today we have largely lost that egalitarian outlook and the spirit of communities. We've forsaken the notion of properties as homes to live in, opting instead to prioritise profiteering from housing.

WaterShed, Lochdon, Isle of Mull by Architects Marcus Lee is listed on Stefi Orazi's website Modernist Estates. Image by Stefi Orazi.

OJ: What has been your own experience with Modernist estates (Barbican vs. your Camden home)?

SO: I now live in a 1970s estate near Hampstead Heath, designed by Benson and Forsyth. It's part of a group of progressive modernist developments built by Camden Council in the 1960s. Being one of the wealthiest London boroughs at the time, and with a socialist agenda, they employed young bright architects including Neave Brown and Peter Tabori to design avant-garde social housing schemes. The Barbican, on the other hand, is a private estate, so in that respect, they are very different. In the Barbican, at least when I lived there, everyone was fairly private, and apart from a courteous nod in the lift, there wasn't much interaction between residents. Where I live now has closer similarities to Golden Lane Estate, as that's also run by the local council. Both estates have a really strong sense of community; you feel you are part of something together, and there is a shared interest. It's easy to get to know neighbours because of that shared interest, which I am not sure you would get on a regular street. But in terms of the actual quality and design of the apartments, such as the attention to detail, the quality of bespoke carpentry, built-in storage, and full-width windows, they've all been fantastic spaces to call home.

A very special thanks to Stefi Orazi. You can find out more about Stefi on her Instagram and websites - here, here and here! Interview by Tiffany Jade. Feature image of The Barbican by Stefi Orazi, and feature image of Golden Lane Estate by Mary Gaudin.